Source: https://jp.wsj.com/articles/when-money-is-no-object-11626060366

デビットカードやクレジットカードなどのカードによる決済は支払い全体の63%を占め、5年前の55%から上昇したとのことです。コロナの影響で衛生的に問題がありそうなキャッシュはどんどん減少傾向のようです。

デビットカードやクレジットカード、オンライン決済やモバイル決済は簡単で確実だし、心配はいらない。インディアナ州ココモでゴルフ中に手を止めて、ネパールのカトマンズで一瞬のうちに買い物をすることもできる。

しかし、どんないいことにも短所があるように、現金を伴わない決済の便利さには短所もある。既にそのせいでお金はためにくく、使いやすくなっている。お金の脱物質化は日常生活においてはいいことのように思えるが、影響は長期に及ぶ可能性がある。私たちはその影響に向き合い始めたばかりだ。

Debit and credit cards, and online and mobile payments, are easy, secure and carefree. You can pause your golf game in Kokomo, Ind., to buy something in Kathmandu, Nepal, in the wink of an eye.

Like all good things, however, the convenience of noncash payment has its bad side. It has already made saving harder and spending easier. The dematerialization of money feels good in our daily lives, but it may have long-term consequences we’ve only begun to face.

私はクレジットカード発行ボーナスと決算ポイントで数十万マイル、ホテルポイントを獲得した経験があるので、クレジットカードは使うべきと思っておりますが、使い過ぎている感覚がなくなる、子供へのお金教育の仕方など、いろいろ弊害が出てきそうです。

ブタの貯金箱、実際にお金を触った経験...

こうした貯金の仕組みはお金に形を与えることで、人々にお金の重みと大切さを実感させた。喜びをあとに取っておくことも楽しみになった。

一方で、お金を使うと、形のある所有物を手放すような気がした。レジ係が買い物をレジに記録してカチーンという音が聞こえると、買ったものは文字通り、あなたの耳と心に刻みこまれた。レジ係が1セントまで数えながらおつりを渡すとき、あなたのお金は計算する上でも、抽象的な意味でも価値があった。

あなたが支払った金額は、お金とそれに注がれた労力以上に大きく感じられた。あなたは買う喜びと同時に支払う痛みも感じた。お金を使うことは手で触れることのできる、ほろ苦い経験だった。

By making money tangible, these savings devices gave it weight and importance—and made deferring gratification feel almost fun.

At the same time, spending money felt like parting with a physical possession. A cashier would “ring you up” at a cash register. As the machine went ka-ching, your purchase literally registered in your ears and mind. As the cashier handed your change back to you, reckoning it to the penny, your money counted—mathematically and metaphorically.

The sum of what you had spent felt even greater than the parts. You felt the pain of paying at the same moment as the pleasure of buying. Spending was tactile and bittersweet

たしかにクレジットカードをタップして支払ったり、ECサイトに番号を入れて購入する際に、痛みは供わない気がします。ので使い過ぎてしまうというのはわかる気がします。

その一方でキャッシュレス決済はあまりに簡単で、買う喜びと支払う痛みの間に緩衝地帯を作り上げてしまった。

クレジットカードを使って欲しいものを買っても、見返りは現金で支払ったときと同じようにすぐさま得られる。しかし代金を支払わなければならないという苦しみはカードの請求書が届くまで感じることはない。

個人的に対策としてMintというアプリで家計簿チェック、家計バランスシートを作ってクレカ負債がどれくらいあるのか日々チェックしております。

下記はMintのスクリーンショット

ミネソタ大学のキャスリーン・ボス教授(マーケティング論)は「支払いにこうした一連の行動が伴わなくなると、支払いがお金と何かを交換することであるという感覚、お金を使うことの重みを感じなくなる」と話す。

現金よりクレジットカードを使う消費者のほうがいくら使ったかを忘れやすく、何を買うかを決めるのに時間をかけず、高い代金を支払うことをいとわず、買い物の回数も多くなることが多くの研究から分かっている。クレジットカード派はさらに、現金派と比べて自分をコントロールすることができず、ジャンクフードや高級品など衝動買いしたくなるものを多く買っている。

“As we move away from paying with those gross motor movements,” says Kathleen Vohs, a marketing professor at the University of Minnesota, “we lose that sense of its being an exchange, the gravity of using money.”

Dozens of studies have shown that consumers using credit cards rather than cash are less likely to remember how much they spent, take less time deciding what to buy, are more willing to pay high prices and make a greater number of purchases. They also exert less self-control, buying more junk food, luxury goods and other impulsive items.

私は怠け者なので、家計簿をつけられないので、家計バランスシートを小まめに記録しクレカ負債が多すぎないかチェックしております。クレカを何枚も持っているので毎日の細かい消費はトラックできません...

我が家の家計BS...

デビットカードとモバイル決済に関する研究でも同様の結果が出ている。最近行われた神経科学の実験では、現金ではなくクレジットカードでお金を支払うと、コカインなどの中毒性薬物を使ったときと同じ脳の報酬中枢が活性化することが分かった。現金を使ったときに痛みを感じるとすれば、クレジットカードを使ったときはおそらく高揚した気分になるのだろう。

Studies on debit cards and mobile payments show similar results. A recent neuroscience experiment found that spending with credit cards, rather than cash, activates the same reward centers of the brain that are triggered by cocaine and other addictive drugs. If spending cash hurts, perhaps using credit makes you high.

これはやばい...改めて自分を律しないと資産形成のペースが遅くなりそうです...

もちろん、現金が使われなくなっているから支出が増えて貯蓄が減っているのか、支出が増えて貯蓄が減っているから現金が使われなくなっているのかは判断が難しい。

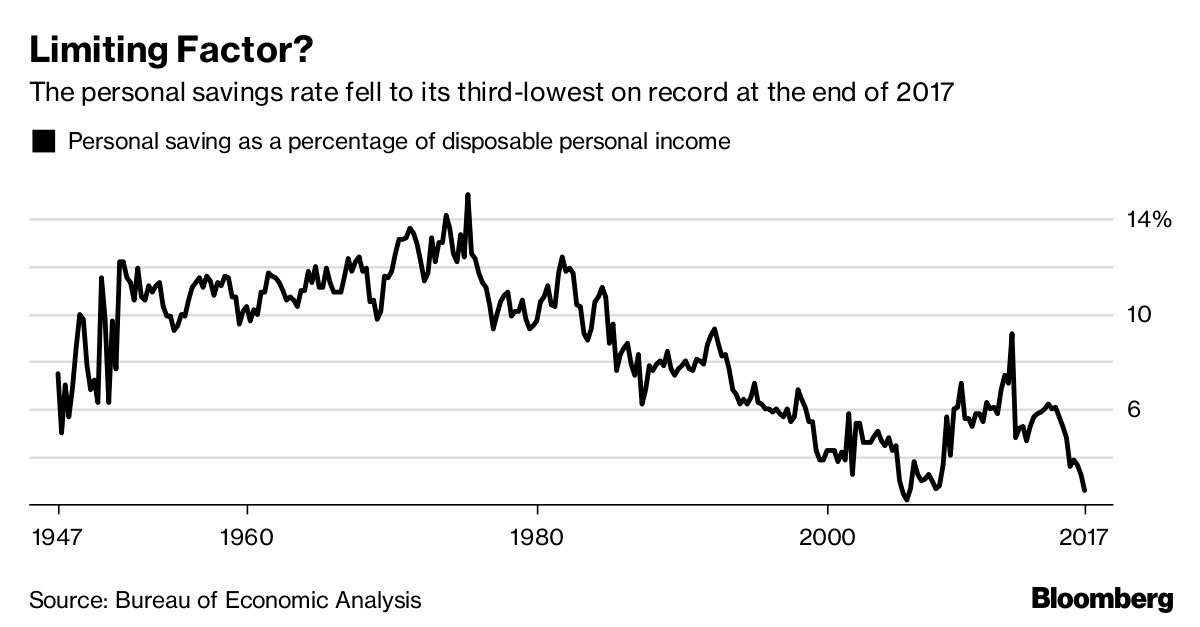

20世紀後半のほとんどの期間、米国人は個人可処分所得の約10%を貯蓄に回していた。しかし1980年代後半には貯蓄が減り始め、1995年の貯蓄率はたった3%だった。貯蓄率は2000年代と2010年代に回復し、その後、コロナ下で経済活動が止まり、経済対策の給付金が支払われると急上昇した。

マサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)の金融経済学者、ジョナサン・パーカー氏によると、米国の長期にわたる貯蓄率の低下を招いた主な要因の一つは1980年代前半以降の金利低下だという。金利が下がると銀行預金の収益率が低下する一方で、借り入れコストは低下し、株や不動産の価値は上昇する。その結果、人々はもっとお金を使ってもいいと感じる。

Of course, it’s hard to say whether people are spending more and saving less because cash is dying—or whether cash is dying because people are spending more and saving less.

For most of the second half of the 20th century, Americans saved roughly 10% of their disposable personal income. In the late 1980s, U.S. consumers began to save less until, by 1995, they saved only 3% of available earnings. That number rebounded in the 2000s and 2010s, then shot up during the pandemic as the economy locked down and people received government stimulus payments.

One of the main factors driving the long-term decline of savings in the U.S. is the fall in interest rates since the early 1980s, says Jonathan Parker, a financial economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Lower interest rates reduce the return on bank accounts, cut the cost of borrowing, and raise the value of stocks and real estate, making people feel they can spend more.

上記コメントに出てくる貯蓄率は下記のグラフで合っているのでしょうか...